Talking about the Pen without talking about the Pen

A couple weeks ago, I spoke to a Museum Studies class at the University of San Francisco. I did not have time to prepare long-form notes in advance of the talk so the following is a reconstruction of what I said with the benefit of hindsight. If these were not my exact words they are what I meant to say.

When I was first invited to speak to this class I asked if there was anything in particular that I should focus on. In the past it's always been about the work that I was involved with to launch The Pen at the Cooper Hewitt. Originally, that was supposed to the the topic for this class but the reality is that there isn't anything new to say about the Pen beyond what I said to this class two years ago.

I am going to talk about the Pen briefly but more in the context of the larger goals we were trying to use the Pen to achieve and some of the other projects, each with similar but distinct motivations, that were happening at the same time. First, though, I am going to start with two strongly held beliefs and a pair of questions.

The first strongly held belief is this: The thing which distinguishes culture and entertainment is the act of revisiting. Importantly entertainment becomes culture all the time but it is the act of revisiting a work of entertainment which causes that transformation to happen. Critically, it is the act of revisiting itself and not the subject of that revisiting which, to use a made-up word, enculturates

a work.

It doesn't really matter whether you, personally, think the time and effort that other people spend studying the nuances and debating the intricacies of global entertainment franchises like Star Wars, Star Trek or the Marvel Cinematic Universe are worthwhile. The commitment that people devote to those endeavours is, I think, the demonstration of the worth and the value those works represent for a community. In short: culture.

Bowling: A Unique American Art Formexhibition 1991

The second strongly held belief is that: The role and the function of cultural heritage institutions (libraries, archives, museums) is to foster revisiting both as a general practice, broadly, and, more specifically, in the context of their collections and holdings. The inability, or the failure, to do so relegates cultural heritage institutions to a position where they are nothing more than one option among many short-term distractions competing for people's time, attention and money. In short: entertainment.

I also happen to believe that, at least in North America, the cultural heritage sector (principally museums) has made revisiting as hard as possible for the most number of people possible. Many people will never visit the same museum more than once and most people will never visit an exhibition, let alone a single object, twice. That is an unpopular opinion or at least not one that people in the sector like talking about openly. There are a lot of complex reasons why we've gotten to this place but the net result is that it has become too expensive and too much of a hassle for too many people and so cultural endeavours (events, artifacts, resources) are generally treated as nothing more than another one and done

experience among many.

We have manufactured the circumstances where we are not so much undoing culture

, which to be clear will keep chugging along with or without cultural heritage institutions, but all of the good work and good will nurtured over the years in those very institutions that were founded to collect, preserve and foster the culture that came before us.

One of the reasons that I like working at a museum in an airport is that the conditions we operate in present a dynamic unique among most museums and cultural heritage institutions: We enjoy repeat visitation by default. While that may not be literally true for literally all of the 58 millions passengers who pass through SFO every year it is true for a substantial number of them. Put another way, if only 10% of those passengers came back to SFO twice we would still have 5.8 million repeat visitations annually. A museum in an airport faces its own unique challenges, not least among them that no one expects to find a museum in an airport. That feels like an idea which can be normalized, though, and with it the desire, value and expectation of revisiting the works on display in our galleries.

But this is not really a talk about museums in airports so on to the questions.

The first question is one I was asked in 2022, on the tenth anniversary of the year I delivered one of the keynote speeches at the National Digital Forum in New Zealand. I was asked to do an interview looking back on the previous decade in the context of all the work we had done at Cooper Hewitt to develop and launch the Pen.

What, I was asked, did I wish I had known at the time that I know now?

I said that I wished I had better understood the dynamics of the long game

in museums.

This is not a flattering thing to say but the reality is that a time-honoured strategy inside museums is simply to wait out

a person or a project that you don't like. The pace at which museums operate, so-called museum time

, and the time it takes to develop and mount individual exhibitions lends itself to a series of overlapping wars of attrition.

There were, and still are, people at the Cooper Hewitt who didn't think the Pen was a good idea. Our team's inability to demonstrate the worth of the project remains one of the very real failures of the project and that failure was compounded by the simple fact that, in museum-time, letting the project operate for five years (that's how long the Pen was on the floor

) was ultimately inconsequential.

On the other hand, five years in the technology world is often enough time to completely up-end, both financially and operationally, what is even considered possible. But, as mentioned, that is still not the speed at which the totality of a museum oscillates and so there is this constant tension trying to demonstrate what is possible between two universes traveling at different speeds. I still don't know what the best way to bridge that gap is. Simply being aware of the problem is no solution but I will argue that it's better than being unaware of it. This is still the landscape in which digital initiatives in the cultural heritage sector operate.

The second question I was asked, more recently, is: What would I tell a group of museum directors the future of museums

looked like? I don't know that my answer ever made it to that, or any, group of museum directors but I would say the same thing now that I said then:

Go look at the new products page on the Adafruit website and extrapolate from there.

The museum sector has become overly-enamoured of the Googles and Disneys and the Apples of the world, each of which enjoys hard-won resources and capabilities, and we desperately want to believe their work is like any other consumer good that can just be ordered off the shelf

and installed in our galleries.

First of all, that betrays a profound lack of understanding about how much work and effort goes in those products. Second, it ignores everything that has become possible for everyone else who doesn't operate inside of the budget affordances and risk tolerances of a global multinational corporation.

Everything you see on Adafruit can be bought, today, with your credit card. In much the same way that underneath all the gild and splendor of so-called luxury mansions you'll still find the same plywood and two-by-fours used in every contemporary home, all the things you see on Adafruit are the same basic components you'll find in every piece of contemporary technology.

Adafruit is not the only company working to make these kinds of components available at affordable prices but what I think sets Adafruit apart has been both their commitment to an open-source model for the hardware and the software they develop and their ability to build on past successes. Adafruit may have begun largely as a supplier of third-party components and custom electronics but they are now designing and manufacturing their own circuit boards and parts in their own facilities in New York City.

In the past I have pointed out that Disney is to the museum sector what Google is to the technology sector, namely an unhelpful distraction

. We, the musuem sector, look at all the ways an enterprise like Disney is able to deploy technology to attract and engage audiences and, more often than not, think that's just something we can get someone to pick up at the dollar store and slap a museum logo on. It is an attitude so completely divorced from the reality of the time, effort and false steps (not to mention capital and operational investments) that it takes a company like Disney to achieve those results that it borders on offensive.

The reason I continue to point to people like Adafruit is because they are doing the work, they are operating at a scale that most closely matches the cultural heritage sector (certainly compared to global multinationals), the results are demonstrable and the museum sector might do well to learn a thing or two from them.

I also want to take a moment and mention this device. This is a product called the Tangara

being developed in Australia. It is a contemporary take on the original iPod music player, complete with a scroll-wheel, made using contemporary circuit boards (the kind you can buy on Adafruit) and 3D printing. It is a crowd-funded project, set to ship their first units later this fall, and entirely open source from the design of the electronics to the software that runs the device.

This thing sells for 250$ which means the unit cost is probably somewhere in the 125$ to 175$ range I actually have no idea but the point is that it's not more than 250$. I find this amazing.

This is what I mean when I talk about the so-called future of museum

being a reflection of the new products page of the Adafruit website. This is especially true given how the sector still holds audio tours, and the devices for delivering those guides, as the pinnacle of all the technological possibilities that might service our mandates. We can debate whether or not audio guides are really the best vehicle for our missions but the point I want to make is that, in 2024, there aren't any good reasons why the sector couldn't produce something like the Tangara purpose-fit for our needs.

Except for the part where nearly every person – and when I say every person

I really mean everyone – who could have done this work or helped train the next group of professionals to tackle these kinds of projects has been driven out of, or away from, the institutions they worked for. Those same organizations have done little or nothing to rebuild any of that capacity. Not that any of those same organizations have stopped spending seven-figure sums on big technology plays which, as often as not, continue to be little more than glorified audio guides.

Speaking of big technology projects, and people who really like audio guides I am going to jump back in time to a three-ish year period, between 2012 and 2015, when Bloomberg Philanthropies funded a trio of projects.

The first was The Pen at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian National Design Museum, a project that I worked on and which, as I mentioned at the beginning of this talk, I have already written and spoken about extensively. I am not going to say much more about it today.

The one thing I want to highlight though is that while the Pen was definitely meant to be a device that generated interest, and press, for the reopening of the museum, in 2014, it also had a much deeper and more important function. Imagine if you could visit the museum

, we used to say, without having to spend your entire museum visit trying to figure out how to remember what you saw during that visit.

That was really the problem we were trying to solve. To provide the means (the Pen) and the infrastructure (the museum's own servers) by which a person could have the confidence that they might, no pun intended, re-visit their visit in such a way that it would allow them concentrate and stay focused on the actual objects on display in the galleries.

The second project was the Brooklyn Museum's Ask Brooklyn.

Ask Brooklyn was a chat-based application for your phone. It was paired with a lot of locative technologies deployed throughout the museum in order to accurately, in a good enough is perfect

kind of way situate you in the galleries. The idea was that you could be standing in front of an artwork and simply take out your phone and start asking questions. Those questions would be relayed to museum staff, seen here in this photo and who you would have passed on your way through the lobby.

This was ten years before anything like ChatGPT. Questions would be answered by actual human beings with a deep understanding of, and commitment to, the Brooklyn Museum's collection. Importantly, and for me this remains the most important thing that Ask Brooklyn achieved, people were talking to visitor services staff and not the curatorial department.

That's a big deal because curators are often nervous and guarded about letting anyone else speak on behalf of the collections they oversee. Asking or expecting curators to staff the Ask Brooklyn application would have been unrealistic. Aside from all the technology challenges that the Ask Brooklyn team had to solve they also established, and normalized, a workflow and a practice whereby everyone was comfortable with not-curators speaking with authority about the collection. I'm not sure whether anyone has done it since.

If you haven't already, I recommend that you read anything that Shelley Bernstein and Sara Devine, or anyone else involved in the project, has written about Ask Brooklyn.

The third project was SFMoMA's SFOMOMA App, another mobile application that visitors would activate using loaner devices that they would pick up with their tickets not, unlike an audio guide. In fact, the SFMOMA App was an audio guide, one that tried to reimagine what an audio guide could be given that state of locative technologies in 2015.

Like Ask Brooklyn, the application worked in concert with a lot of indoor location infrastructure to follow

you around and play narrative content about individual works or artists without the need for visitors to enter a code or, worse, an accession number. It featured the ability for two people to pair their respective devices and listen to the same guides in concert, an effort to promote the appreciation of the museum's collection as a shared and communal experience.

The SFMOMA App was also a cautionary tale about the perils of working on the bleeding edge of technology and with the commercial sector, even in a city like San Francisco where both things are often treated as gospel. Ten years later it's clear that what SFMoMA was trying to do with communal locative experiences was on the right track. Nearly everything the SFMoMA application tried to do is now available natively in the iOS and Android mobile operating systems but ten years ago it just wasn't and the application suffered accordingly.

SFMoMA developed their application in close collaboration with a company called Detour, a start-up focussed on developing locative audio tours for indoor and outdoor spaces. I don't know what the exact details of their collaboration were but what is known is that, as is the way with a lot of start-ups, Detour never really took off and was eventually sold to Bose. It wasn't long before Bose eventually shuttered the entire Detour project and with it SFMoMA's mobile application which was entirely dependent on external partners to operate and develop.

Those three projects were all part of the same funding push by Bloomberg Philanthropies in the first half of the twenty-teens. None of them, including the Pen which managed to survive until the COVID-19 pandemic, are in active use anymore. There is a fourth project, not part of that funding cycle which was launched five years later: The Lens.

The Lens was developed as part of the Australian Center for the Moving Image's (ACMI) re-opening in 2021. I mention it because it builds on all the lessons, good and bad, of the projects I've just told you about. I'm going to show the introductory video that ACMI produced for the Lens so that you can see how a project that tried to learn from and overcome all the challenge of these first three projects articulates itself:

If the Lens looks suspiciously like the Pen, that's because it is. Seb Chan, who was Chief Experience Officer and is now CEO at ACMI when the Lens was launched, was also the head of the Digital and Emerging Technology group at Cooper Hewitt when the Pen was created. The Lens tries to address many of the problems – chief among them financial and logistical – that putting all the technology in the hands of visitors rather than embedding it in the (museum) building itself introduces.

Seb and I have a running debate about the merits of each approach. Each has it's own shortcomings, each presents its own opportunities. I can, however, appreciate that most if not all the opportunities that the Pen made possible, by virtue of its size and mobility, were never capitalized on during five years it was available to visitors.

While each of those projects was unique in their own right they have shared a common motivational arc. What all of these projects have in common was, and is, an effort to try and give visitors a great sense of agency.

To use the technology at hand, both metaphorically and literally in people's pockets, to allow them to be more active participants with the museum they were visiting. There is a whole other question to be had about how successful any of these projects have been at achieving those goals but, for now, I want to focus on one specific place where I think they have all fallen short.

What all of these projects have failed to do is to embrace all the technologies they deployed to do anything meaningful on either side of the museum itself. I generally refer to this as the following you out of the building

problem.

Some projects, like the SFMOMA app, didn't do that because they were tailor-fit to the gallery spaces themselves. Maybe a roaming off-site SFMOMA app was always in the cards and might have happened if Detour had not been sold.

Other projects, like Ask Brooklyn were geo-fenced to the museum property, by design. Brooklyn Museum has always seen itself as a museum by and for its local community. At the time the Ask Brooklyn project was launched there was a renewed push to embrace the museum visit as an in-person, rather than a virtual, experience. As a consequence, the conversations you had with staff about the work you saw were only visible when you were in-site.

At Cooper Hewitt, the post-visit experience

just never happened. It's not like we didn't know it was both necessary and the obvious next step following the launch of the Pen but, for a variety of reasons not uncommon in many museums, that work never got started.

ACMI, having watched and learned from all the projects that preceded the Lens, has done better than the rest. Which is to say they've at least done something but it still doesn't feel like it – where it

is the ability to use all these digital technologies to actively bookend an in-person museu visits in an ongoing and meaningful fashion – is given the attention it warrants.

All in all, it's been a kind of two steps forwards, one step backwards

process. All four projects have demonstrated that there is an appetite for tools to promote and enable increased agency during a museum visit. To varying degrees, we have worked out or at least learned valuable lessons in how to manage the financial and operation requirements that these projects incur, although I think there is probably still a healthy (and necessary) debate to be had on this last point.

But in practice all of this work is still confined to the boundary of the museum campus. This at a time when you can literally order cat litter to be delivered to your home, on your phone, from the beach. Not because anyone wants to have a cat-litter-ordering

experience but because a) not ordering cat litter will end badly for everyone b) having to schlep cat litter around is no fun and c) staying on the beach is fun.

It is hard to overstate how completely out of touch the museum sector seems to be with what contemporary technologies make possible, how those possibilities are changing people's expectations and where those expectations now intersect with the museum sector itself. More and more, I find myself asking: What is the functional equivalent of ordering cat litter on the beach for museums?

In order to talk about the following you out of the building

problem and, more specifically, about how that problem might be addressed in 2024 using a relatively nascent set of technologies I need to take brief detour...

...in the Jargon-o-sphere. I want to talk about some promising efforts in the social messaging space and how these initiatives might better serve museums and their programming. Unfortunately there is no way to talk about these things, yet, without using language and terms that are still largely foreign to most people. I will try to be brief and succinct in describing them.

The terms that follow tend to evoke strong opinions and are not infrequently the subject of vigorous debate but these names are, as I write this, the lingua franca of the topic at hand.

- Decentralized A “decentralized” service, as the name implies, exists in contrast to a “centralized” service. Centralized services are ones where all the interactions between participants happen inside the boundaries of the platform operating that service. For example, services like Facebook, Twitter or TikTok are all considered “centralized”. The most easily recognizable “decentralized” service is email where any number of providers (Gmail, Hotmail, etc.) can interoperate with one another using a variety of different clients (Gmail, Outlook, Apple Mail, etc.)

- ActivityPub A set of standards and protocols for exchanging (sending, receiving and propagating) messages and related interactions in a decentralized manner. Although ActivityPub is not limited to “social networking” or “social messaging” these kinds of activities are still the most common use cases.

- Mastodon An open-source software project allow communities to host their own social networking websites that, by virtue of implementing the ActivityPub standards, are able to interoperate with other Mastodon instances (and other ActivityPub services).

- Fediverse This is a common term used to describe the “federated universe” of decentralized services which are able to interact with one another.

So, an abbreviated version of the contemporary fediverse

looks like this:

- Around the time that the large social networking websites (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) started gaining traction a number of people asked: Why isn't it possible to exchanges these kinds of messages (notes, photos, etc.) in a

decentralized

fashion, like with email, instead of only being able to do so with in the confines of a specific platform or vendor? - Some of those people started working on a variety of protocols to do that and one of the results of that work was the ActivityPub specification which is not an application itself but the standards by which two or more applications might communicate in a decentralized fashion.

- All of this work received renewed attention in 2016 and then again in 2022. There is a sense, or maybe just a hope, that the second round of interest will not wane as quickly as the first.

- One of the projects to emerge from that first round of interest was Mastodon which is where much, if not most, of the effort and attention in this second round of interest is being focused. That is due in large part to the fact that Mastodon has structured itself in a way that it has been to survive this long and, in that time, has devoted considerable attention to developing an application that people who don't care to sweat the technical details can actually (mostly) use.

- More recently a number of existing services have start integrating the ActivityPub standards in to their applications, mostly notably Meta's Threads app. At the moment you can only follow Threads accounts in Mastodon but Meta has pledged to make it possible to follow Mastodon accounts in Threads by the end of the year.

For the purposes of this talk there are two immediate take-aways. The first is that there a growing network of interoperable Twitter-like applications which people (people who don't want to think about standards and protocols, or participate in the tire-fire that social media sites operated by the big technology companies) can use. The second take-away is about the standards and protocols that have been created and is important for the next thing I want to discuss.

If you remember nothing else, remember that what makes protocols like ActivityPub important is that they are the technical means to make possible that which the "marketplace" can't or won't allow.

For example, in the spring of 2012 I got access to a list of 50,000 artworks, and their corresponding webpages, from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Shortly afterwards I emailed the support team at Foursquare, at the time still a social location-sharing website, and asked whether they would have any concerns if I used that list to create 50,000 “venues” on their platform; one venue for each artwork in the MoMA collection. If people were already actively competing to become “mayor” of their local coffee shop it didn’t seem like much a stretch to imagine that people would do the same for their favorite works of art on display at MoMA. Foursquare politely asked me not to do that. I was disappointed but not entirely surprised. Aside from all the other considerations having that many “venues” all clustered within the space of a single building, even a building as large as MoMA, likely would have introduced a host of interface problems for the service.

A couple years later, after I had left the Cooper Hewitt, I was out with a friend who worked for Twitter and I asked them whether it would have been possible for the museum to “create 200,000 Twitter accounts, one for each object in the Cooper Hewitt’s collection”. My friend looked at me for a moment, laughed, and then simply said: No.

Which is kind of weird, really, since all I was proposing was the creation of just another army of sock puppet accounts

, many of which already exist and operate openly on these services today, but in the service of a museum collection rather than ponzi schemes, intimidation or worse.

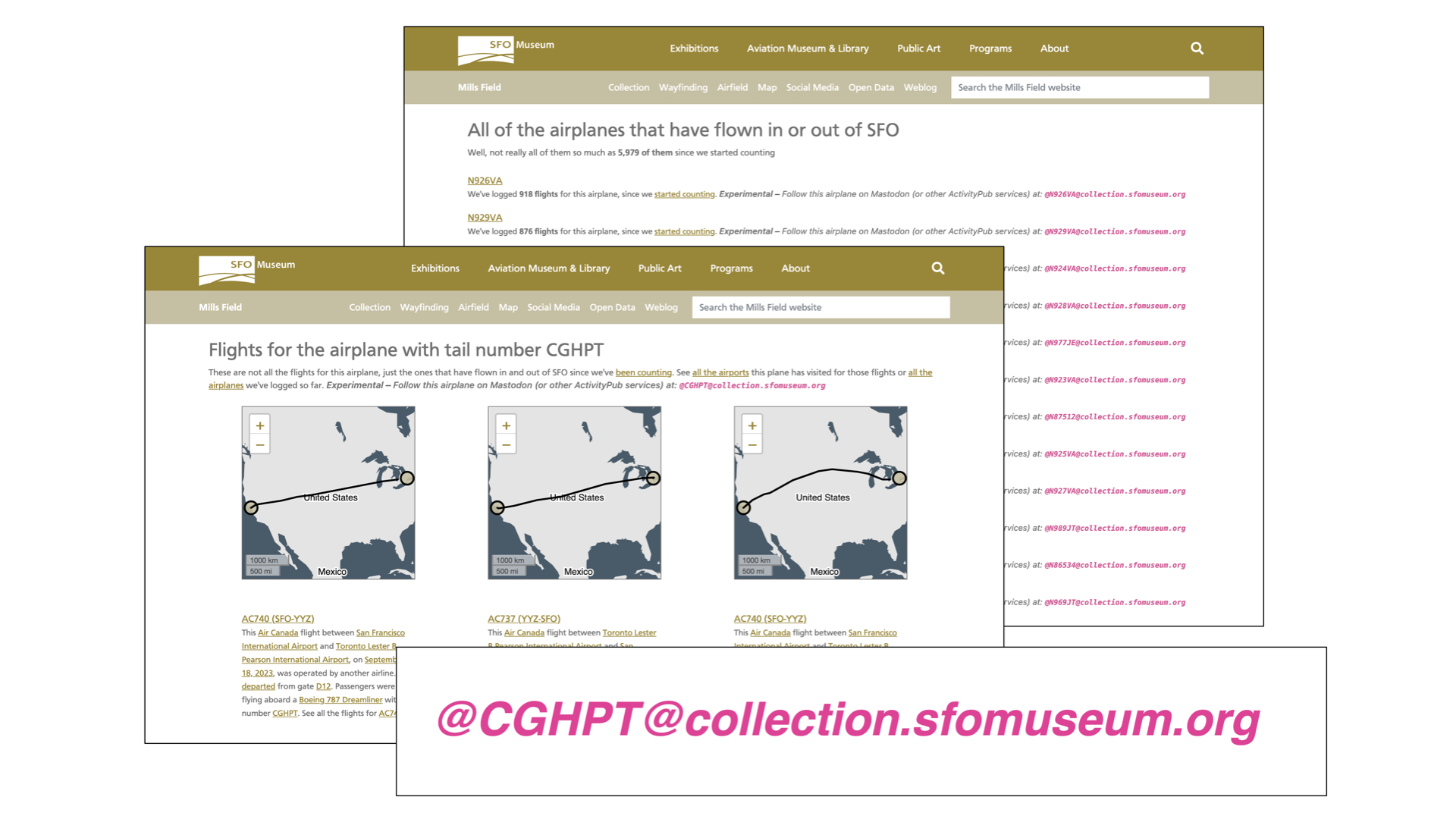

The reason I am telling you all of this is that SFO Museum has written it's own limited ActivityPub server implementation and we have, in fact, created an ActivityPub account – a social media, account – for every object in our collection. They don't do anything yet, which is something I'll talk about more shortly, because I only just finished creating them in time for this class.

We were able to do this because these accounts operate on servers we control. We didn't have to ask permission to do this or ask someone else to shoulder the burden of those accounts. And, as I've already mentioned, because of the underlying standards and protocols being used these accounts are guaranteed to work with other ActivityPub services.

Before creating an account for every object we first created social media accounts for 6,000 unique aircraft tailnumbers that have flown in and out of SFO. The next time you are the airport and are looking out at an airplane on the airfield there is a good chance it will an ActivityPub account.

SFO Museum has been actively harvesting data for flights in and out of SFO since 2019. We have data reaching back as far as 2006 and for the last five years we have also been recording the tailnumbers of individual airplanes. At present we have captured about 6,000 unique tailnumbers and over 750,000 flights that those planes have taken.

Every day, we iterate through the list of tailnumbers picking a random flight that each airplane flew. For any given flight we know the origin and destination airport as well as the operating airline and from that list we pick a random facet and then look for a related object in the collection.

This data then serves as the basis for a new (ActivityPub) post:

On {DATE} I flew between {ORIGIN AIRPORT} and {DESTINATION AIRPORT} as {AIRLINE AND FLIGHT NUMBER}. Here is an object from the SFO Museum Aviation Collection involving {FACET} – {LINK}

If most people don't know that there is a museum at SFO even fewer of them know that that same museum also has a permanent collection of over 160,000 aviation-related objects. We have also created ActivityPub accounts for airports related to SFO and we'll do airlines soon. The goal here is to make good on the idea that no part of a visit to SFO, whether it's the place you are traveling to or the airline you are flying with or the actual airplane you are flying on, doesn't have a straight line back to the SFO Museum collection.

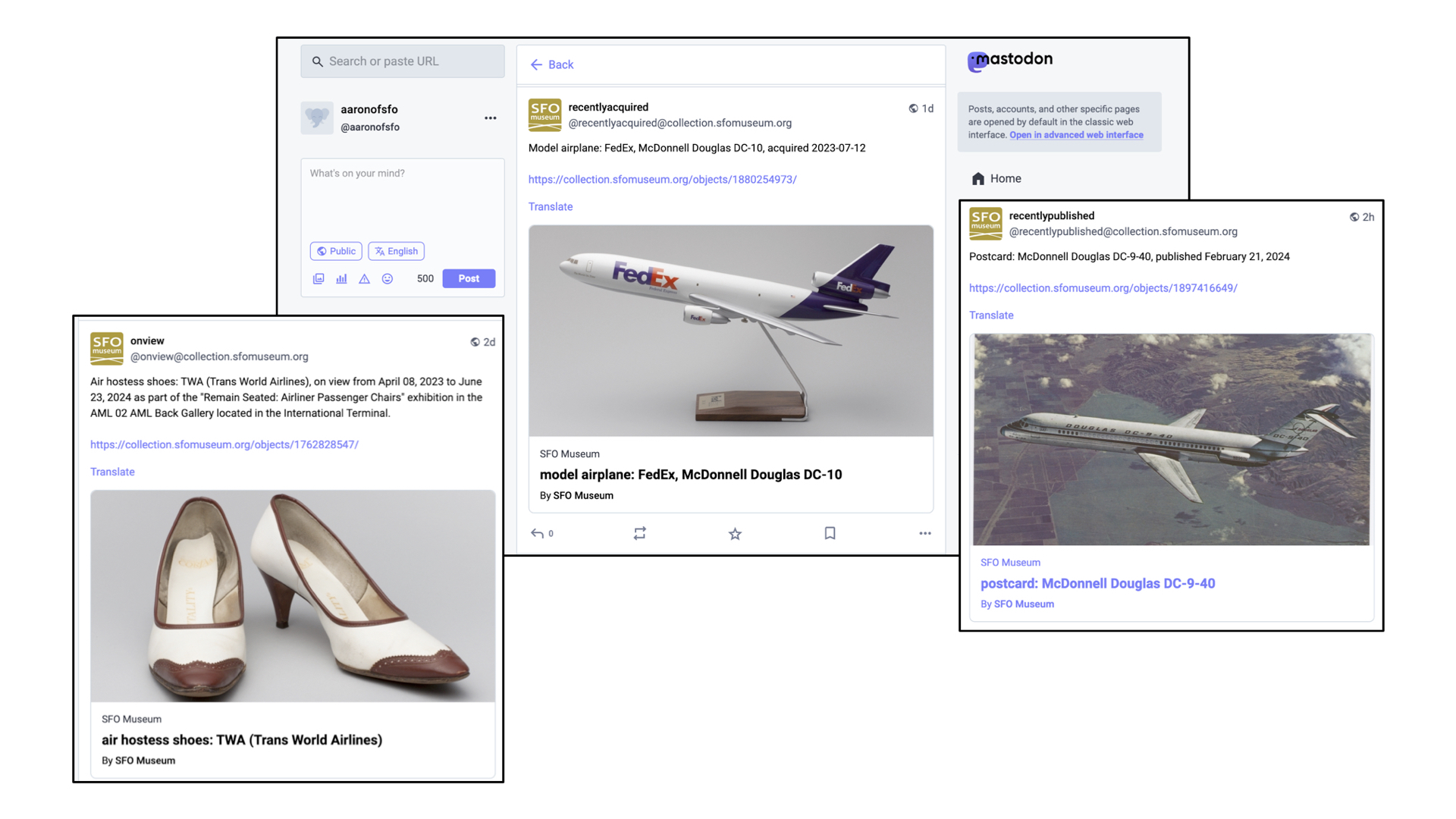

We have also created ActivityPub accounts for all the terminals, past and present, at SFO. Like the tailnumber accounts, the terminal accounts are automated and everyday they post a random installation photo from one of the over 1,400 exhibitions SFO Museum has mounted since 1980. If most people don't know that there is a museum at SFO even fewer of them realize that the museum has existed for over 40 years let alone put on that many exhibits.

And there are a growing number of accounts which simply mirror things for which there are already existing syndication-style feeds: Random objects currently on view in the airport terminals, objects which have recently been acquired by the museum and objects that have recently been published to the SFO Museum Aviation Collection website. The museum has a permanent collection of over 160,000 objects but only a third of them are online so the more ways we have to draw people's attention to those works is good.

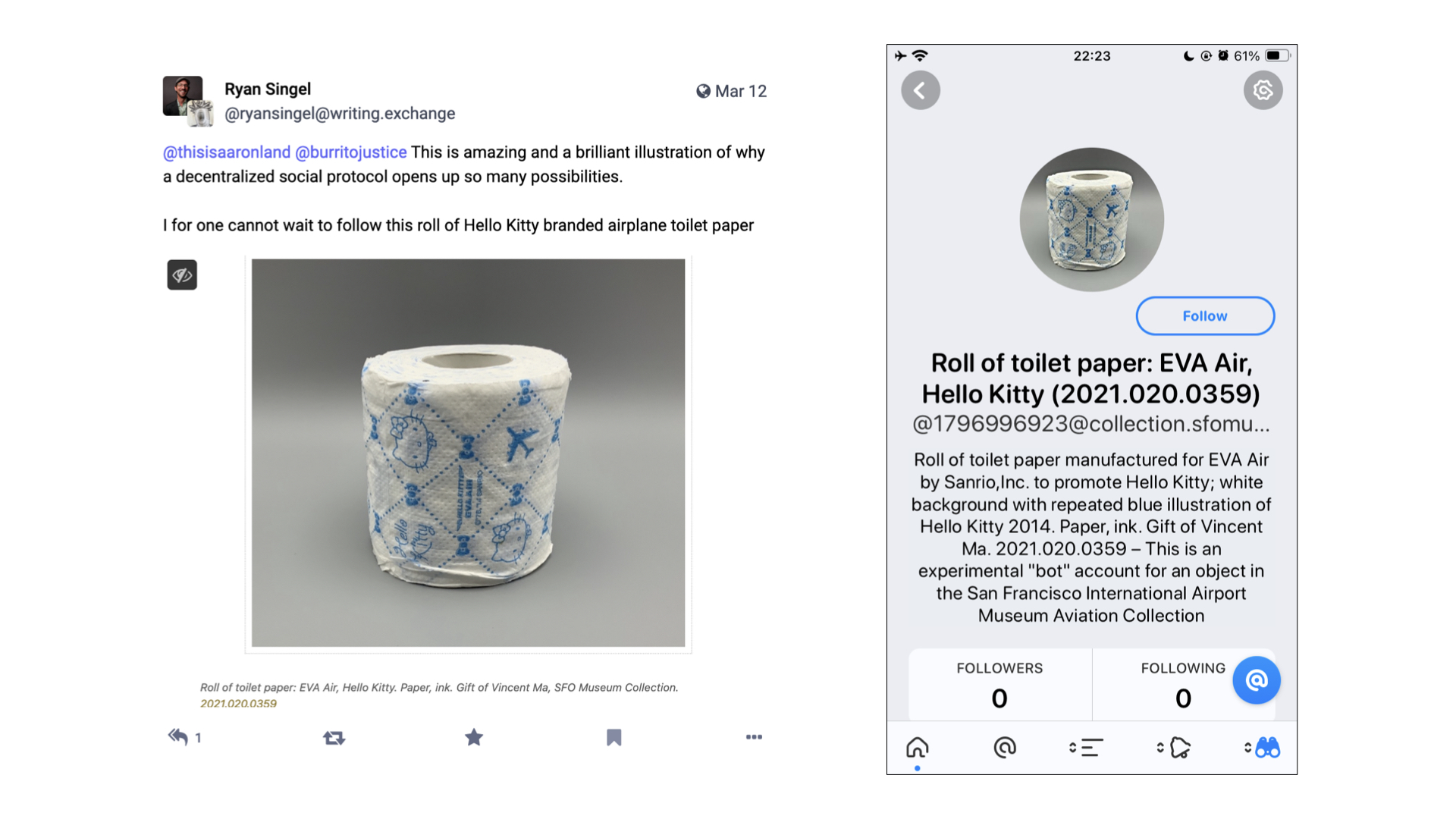

And, as I've mentioned, there are now ActivityPub accounts for each object published to the collection website including this handsome roll of Hello Kitty toilet paper. If that seems absurd, or provocative, I will just remind you that people already take pictures of wall labels, or selfies of themselves in front of artworks, as a way to remember things all the time.

In the blog post that accompanied the launch of our ActivityPub integration I said:

Importantly, these [accounts] serve as a kind of vehicle by which we are able to guarantee that the objects in our collection, which by virtue of their inclusion we argue means they are worthy of repeated consideration, can enjoy a kind of repeat visitation. Even if that revisitation is virtual it fosters the practice of seeing, and re-seeing, the objects in our collections more than once.

What I didn't say in that blog post, but what I really mean is:

It's basically... the Pen! If that sounds even more absurd, or provocative, than a social media account for a roll of toilet paper let me explain.

The Pen was, fundamentally, the world's most complicated physical bookmarking system. In 2015, it turns out that the Pen and all its associated infrastructure was the least amount of hardware necessary to make bookmarking-by-touch

possible. The point of the Pen was not to deploy hardware and electronics for the sake of it but because the Pen is what made collecting an object by touching its wall label a tangible reality. The point of collecting by touch was not so much to have a touch experience

but because touch was (and probably still is) the easiest, most intuitive and least distracting way to record interest in something.

The Pen is also a reflection of the technology landscape of its time. More than a few people have asked us why we didn't just make a mobile application to do all the same things that the Pen did. There are a number of answers to that question but the simplest and shortest one is that neither the hardware nor the software for interacting for NFC tags was available in most iPhones at the time.

Fast forward ten years and the electronics for doing near-field interactions are common place as are sophisticated on-device text and optical-character recognition systems. So imagine a set up akin to the Pen where every wall label embeds not just an object ID but an ActivityPub address for that object which can be subscribed to, in the application of your choosing, by scanning it with your phone. And that's it. That's all you have to do. You can sit back and wait for that object to start talking to you or, if a museum has invested in an Ask Brooklyn style infrastructure, you could even start talking

to it.

Is it great that you still need to use your phone to do this? It's not, really, and at least initially the requirement for an account on an ActivityPub-compatible service would present a substantial barrier to entry for a lot of people. There is also the simple brass-tacks problem that there is no equivalent of the mailto:// URI scheme for social messaging accounts so even if your phone scanned an ActivityPub account, embedded in a wall label, it probably wouldn't know what to do with it.

My point here is not that ActivityPub accounts represent a captial-S solution to all our problems so much as an improvement, or a refinement, to a series of long-standing challenges and compromises that museum staff and visitors, alike, are forced to travel. While still not perfect these things feel, to me, like they are quantifiably better than yesterday

.

But, what then, do these accounts say? It's a problem I have alluded to a few times already. One of the challenges that digital technologies has made manifest in cultural heritage organizations is that there is more stuff than anyone has the time, attention or ability to devote to.

In the past, before networked computers and compendiums of information like Wikipedia (or frankly, Amazon) changed people's expectations of what can and should be taken for granted, the cultural heritage sector dealt with this problem by hiding it in a flurry of words and never letting anyone see all the things stacked on shelves in the backroom. But people's expectations have changed and coupled with the calls for open access around our collections suddenly all that stuff, much of it uncataloged and unresearched, is seeing the light of day without much context.

There are two things to note here. First, it's not like the curators and scholars working today are slacking off. Most of them are genuinely booked up, committed to their practice and their research, and only have so much time to devote to a roll of airline toilet paper, for example. Second, there is a reason why every vendor in the museum-space has a line-item in every project they do for a small army of content producers

.

So, what do we do? One option would be to just go back to the old days when all museums ever shared were perfect

records (few of which, it should be noted, have ever survived the scrutiny of time and changing norms). I don't want to happen nor do I think it will unless there is a corresponding shift in the wider expectations we have in the rest of our lives (you know, climate change and civilization collapse... and stuff).

When I have been asked what should have followed the release of the Pen I have always said the same thing: The curatorial file

. That's the shorthand name for the folders of notes and references that curators keep for artists, exhibitions and even individual objects. These files are a gold mine of interesting facts, associations and hypotheses which inform how a curator approaches a subject. I do not want to suggest that the curatorial file should be subjected to any kind of wholesale radical transparency

. There are always going to be some things which can't or shouldn't be made radically transparent

. I do want to suggest, however, that probably sixty to seventy percent of any given curatorial file could be made public and that this information would find a ready audience.

The reason I am talking about this now is to point out that one of things that makes a technology like ActivityPub interesting is that it provides a working implementation for the means by which that information, in all the curatorial files in all the museums, might be distributed. Crucially, it provides the means to do so without the Faustian bargains that we've seen the earlier social media platforms extract in exchange for reach and access.

What I am suggesting, though, represents a pretty substantial shift in contemporary museum practice. For anything like this to gain traction will probably require a sustained amount of time and effort to normalize inside museums. It will be necessary to develop the tools and interfaces which best allow curators (and registrars and really anyone involved in museum production

) to integrate the idea of a social media account (a channel) for each object in a collection in to their daily practice and that's probably not going to happen quickly. I absolutely think its worth doing but I want to realistic about what it will take to get there.

In the meantime I also hope that I will be proven wrong and will see something like this taken up with reckless abandon sooner rather than later.

But, it's 2024 and we are in San Francisco so obviously the answer to all of these questions is... algorithmically generated content

, right?

Here's a game I like to play from time to time. I take a random object from the SFO Museum Aviation Collection and feed its description in to an AI image generator just to see what comes out the other end. On the left is a poster advertising milk featuring the pilot Emilia Earhart and some of her contemportaries. On the right is a depiction of the museum registrar's description of that object as imagined by a machine learning system:

Poster produced by unknown organization as advertisement for milk; light blue background with black and white images of Amelia Earhart, Bert Acosta, and Emile Burgin, each holding a glass of milk.

So, you know... MILK EAFARK

, right?

With a few exceptions, most conversations about machine learning and artificial intelligence treat the subject as a simple polarity: The machines will rise up and destroy humanity or the machines will empower us to achieve our inherent grace previously denied to us by the mundane realities and petty grievances of life. In between is the silence of everyone else forced to listen to a pair of carnival barkers battle for attention.

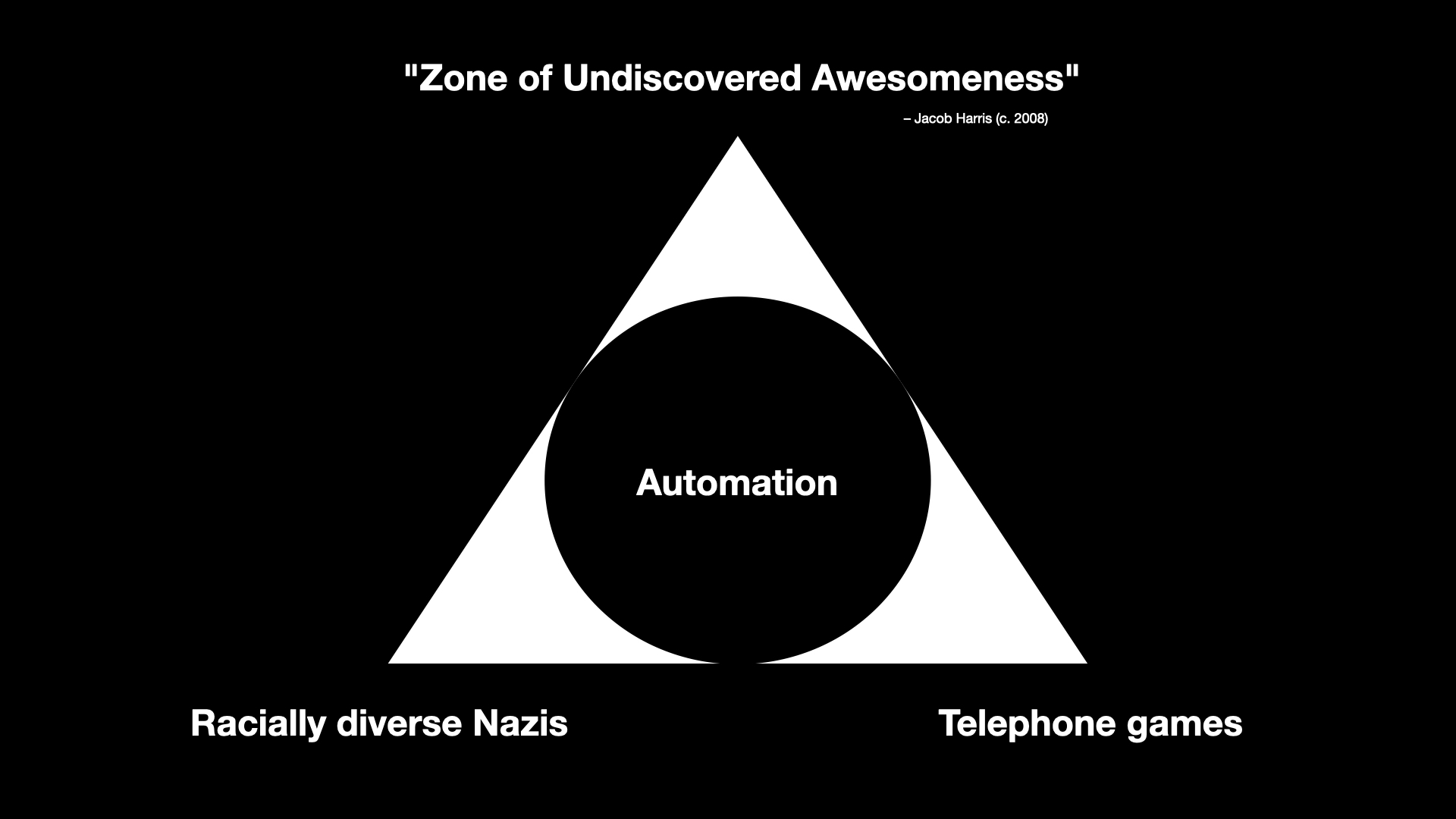

I want to start by suggesting that there is at least one commonality that bridges both the hopes and fears around machine learning technologies: Automation, and the speed with which the impacts of these technologies can be applied.

So, rather than things a two-dimensional binary equation I try to look at it more as a three-dimensional pyramid with one of the four corners being automation. It may be the case the automation also occupies most of the volume of the pyramid but it still leaves three other corners to describe this thing we call artificial intelligence

, and in particular large language models, which is suddenly everywhere we look these days.

The first corner, the one I think most people are familiar with, is the domain of what I refer to as telephone games

. Wikipedia describes the telephone game this way:

Players form a line or circle, and the first player comes up with a message and whispers it to the ear of the second person in the line. The second player repeats the message to the third player, and so on. When the last player is reached, they announce the message they just heard, to the entire group. The first person then compares the original message with the final version. Although the objective is to pass around the message without it becoming garbled along the way, part of the enjoyment is that, regardless, this usually ends up happening. Errors typically accumulate in the retellings, so the statement announced by the last player differs significantly from that of the first player, usually with amusing or humorous effect. Reasons for changes include anxiousness or impatience, erroneous corrections, or the difficult-to-understand mechanism of whispering.

Which, coincidentally, is not very far from how most large language model actually work. This is territory not so much of good enough is perfect

as good enough is good enough

. It is the territory of acceptable mediocrity and saccharine platitudes. It's not necessary bad, or even wrong, but it's also not very good either.

In the pursuit of short-term economic gains, lots of people are going to use this corner of the pyramid to put a lot of other people out of work and not lose sleep over that or the fact that these synthetic replacements will be worse for everyone (except for them) than whatever they are replacing. Basically everything we already dislike about our current economic systems, just super-charged.

Since this is a museum studies class it warrants mentioning that this corner of the pyramid is also the place where when you ask it to describe works of art it returns an aggregate of all the worst practices and learned behaviours parroted in every first-year art history paper ever written. Because the world really needs more of that, right?

In fairness, Bruce Wyman is doing good and valuable work to figure out how to make large language models be not-so-awful at describing and classifying works of art, as well as sentiment analysis and querying structured data (in the service of a yet to be announced Catalogue raisonné). If these are subjects which interest you then his work is worth a look.

Looking at the pyramid so far, we've basically created systems for automating cocktail party conversations.

The third corner of the pyramid is where everything goes wrong and gets ugly. Currently this is epitomized by Google's Gemini AI image generation tool which happily started producing images of... racially diverse Nazis.

It would be easy to get side-tracked enumerating and ranking all the ways that machine learning technologies have fundamentally misunderstood that which they claim to understand to produce the firehose of dumb, awful and abusive shit that we are all forced to weather now. Because I am talking about things as a pyramid I will point out that Gemini not only generated racially, diverse Nazis but did so drifting in to the corner of saccharine platitudes rendering them in the warm donut-glow of a Hallmark card which, if we're going to be forced to choose, is somehow better

than all the deep-fake revenge-porn also now being cranked out in to the world, I guess?

But really that's a bit like reframing the question to ask whether it's better to be shat on or vomited on, rather than demanding to know why either is happening in the first place.

There is already enough cognitive dissonance in the grotesque cruelty of Google's images but it is taken to new heights if you've ever read Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow. This is a passage from an article looking back on the novel 50 years after its publication which describes one of the book's sub-plots:

A military operation called Operation Black Wing uses forged documents and a staged film reel to invent an African rocket troop called the Schwarzkommando, an attempt at psychological warfare playing on Germany’s fear of the South African Herero people, whom they tried to wipe out forty years earlier. But then, it turns out that the Schwarzkommando are real...

To recap: The German massacre of the Herero people is an historical fact which was introduced in to a work of fiction in the context of a fake psychological operation that, in the fictional world of the novel, turns out to be real. That's basically Thomas Pynchon in a nutshell, for you, and one reason I am not surprised this book isn't ever mentioned in the context of the Google image fiasco.

Other reasons include the fact that very few people have ever managed to finish reading the book, the question of whether or not this kind of narrative device (the shock value of an African Nazi commando group) really passes the smell test

anymore and the awkward reality that if Gravity's Rainbow were published today most people would probably think it had been written by a large language model.

And there's one other reason: It is almost certain that Gravity's Rainbow, one among countless other works of fiction, was used without permission, guidance or recompense to train the large language models that are now employed to make manifest all our hopes and desires. From the perspective of a mathematical equation, because remember it's all still just iterative math under the hood, racially diverse Nazis probably seem as real

as anything else.

It's not like this is a new phenomenon either. In 2015 the photo-sharing website Flickr started to add algorithmically generated tags, derived from work that the Yahoo! Research Team had been pursuing, to people's photos. That project lasted about a day, if it even lasted that long, after people discovered that photos of people of African descent were being labeled monkey

and ape

while photos of Auschwitz and the other Nazi concentration camps were cheerfully being labeled train station

and jungle gym

. This was almost 10 years ago. If that fact isn't already depressing enough consider that all of these things have been automated and sped up by at least several orders of magnitude now.

That leaves one final corner and it is the corner where a lot of smart, thoughtful and intelligent people can be found working with and investigating what all of these technologies make possible in ways that aren't boring, awful or both.

I am not sure that this corner of the pyramid isn't more than a tiny percentage of the overall volume which, as I've just finished describing, leaves a lot to be desired. For example, I haven't even mentioned the question of the environmental impact necessary to sustain these technologies. Maybe there is a world where the benefits outweigh the costs but is that really true of something which is mostly bad and tilts towards terrible?

Still, it would be unfair and disingenuous not to acknowledge that there is some interesting and thought-provoking work and analysis happening and so I have dubbed this corner of the pyramid the Zone of Undiscovered Awesomeness

.

The phrase is borrowed from a presentation that Jacob Harris did a number of years ago. Jacob worked for the New York Times and he was talking about the kinds of possibilities that opening up the paper's archives to programatic access might afford. What other ways of telling and interacting with the all the stories the paper had published over the years (essentially a re-telling

) would that access, and importantly an access which could be automated, allow?

This is the motivating space, I think, for a lot of people when it comes to large language models and other machine learning technologies. Is it possible, they ask, to use advances in automation to walk right up to but not cross the lines that delineate good from bad and what does that allow to do which was previously impossible?

If your immediate reaction is to question how that delineation between good

and bad

is determined my answer is an emphatic Yes!

. For the sake of brevity, I am assuming a kind of all-emcompassing good intentions

because the point I am trying to make is that I do not believe that (these) people's motivations in pursuing their work are born out of malice.

It does, however, lead people to say things like this:

LLMs are like a trained circus bear that can make you porridge in your kitchen. It's a miracle that it's able to do it at all, but watch out because no matter how well they can act like a human on some tasks, they're still a wild animal. They might ransack your kitchen, and they could kill you, accidentally or intentionally!

This is sort of the software equivalent of Samsung saying that it was a miracle their exploding Note 7 tablets even worked at all and that the very real possibility they might burst in to flames in your hands was an acceptable trade-off.

The reason I include this quote is because I think it highlights an important aspect of the work happening in this part of the pyramid: Tolerance. Not tolerance for the extremes but a willingness to embrace the unexpected, the incorrect and the weird. This is where I am going to start bringing the talk back around to the subject of museums.

Eventually.

This is an image from a blog post by Harper Reed titled Our Office Avatar pt 1: The office is talking shit again

. The blog post describes how Reed installed a number of sensors (the kinds of sensors you can buy from Adafruit) in his office which are then used as the input to a large language model that has been instructed to generate messages about the data its received which are sent back to the people in the office by way of a chatbot.

The prompt used to generate the messages is explicitly designed to be funny, even snarky:

Interpret the co2 and air quality results into prose. Don't just return the values. Remember to use plain english. Have a playful personality. Use emojis. Be a bit like Hunter S Thompson.

More importantly, I think, is that the prompt has been crafted in such a way that its audience knows and even expects the messages to be weird, wrong or maybe even just a little bit offensive. The goal is not, I assume, to create a bot that insults people but at the same time there is an understanding, a tolerance, that it might stray outside of people's expectations and in doing so produce a novel result. We sometimes just call this play

.

The important part, for me, is not an office interpreting environmental sensors. What's important is the demonstration of what is possible today combining historical data, real-time data, inexpensive hardware and automation to produce novel interactions or simply to create the kinds interactions which foster the revisiting of things overlooked in the rush of day-to-day life. Kind of like museum collections, right?

One of the best examples of these ideas, a project called Hello Lamp Post, predates artificial intelligence and large language models by a decade. I'm going to play the entire 5-minute promotional video for Hello Lamp Post because it does such a good job of explaining the project and what its creators were trying to accomplish.

Why wouldn't a museum do something like this for its collection?

The common theme in all of these projects is giving voice to things and using humour, or lightheartedness, as a way to draw attention to those voices.

There's a comment that Tom Armitage makes at the beginning of the Hello, Lamp Post video that I think bears repeating:

There's a lot of value engaging with people at a playful level and then using that trust you build, and their enjoyment, to go actually quite interesting and profound places.

Play is both an end, in and of itself, but also the vehicle by which you move beyond play.

Spanking Catlate 19th–early 20th century

That's an idea which has been circulating for a while but the challenge for museums is this:

Play

it treated like a four-letter word. Obviously, the idea that play, or worse fun

, works at cross-purposes to thoughtful, scholarly consideration of our collections and our programming is less true in some museums than others. But I don't think it's entirely untrue either.

If you've ever had the chance to sit around the table over dinner, or better drinks, with a group of curators you will know that the tenor of the conversation – the tenor but not the substance – is demonstrably different, some might even say more fun

, than if that same conversation were happening at a conference or in a peer-reviewed publication. But why?

As usual, there are a lot of overlapping and competing reasons why and there isn't time to do them all justice today. I will just say this: I don't think we can discount the fact that the economic realities of the cultural heritage sector have started to affect its output in ways that are fundamentally detrimental to its stated mission (if you understand that mission to be in the service of the many and not just the few).

Specifically, that the scarcity of funding and of available opportunities or, depending on your point of view, the over-saturation of people wanting to work in the sector has created an environment where the discourse has become overly deliberate and constrained because those boundaries are understood to be how and where positions are rewarded or challenged.

Here's the problem with that dynamic: Most people outside the museum sector don't have any idea what anyone inside the sector is saying anymore. They hear the words but in all those sounds there is no meaning which they can decipher.

I want to emphasize that last point: which they can decipher. There is (usually) meaning in the formal language of museums and its practitioners but unless you've gone to art school, where you learned to internalize the discourse or at least filter out the jargon, that language is... well, not fun.

The argument I am trying to make is not (necessarily) that the structures and dictates of scholarly rigour should be replaced by fun, or by play, but that the latter are real and valuable means to introduce and acclimate people to the former. The idea which needs to be challenged is that by making light of, or even joking about, our collections we are not serious

in our work. The entire premise is insane, really, but I don't think I am wrong when I say this is still a commonly held belief.

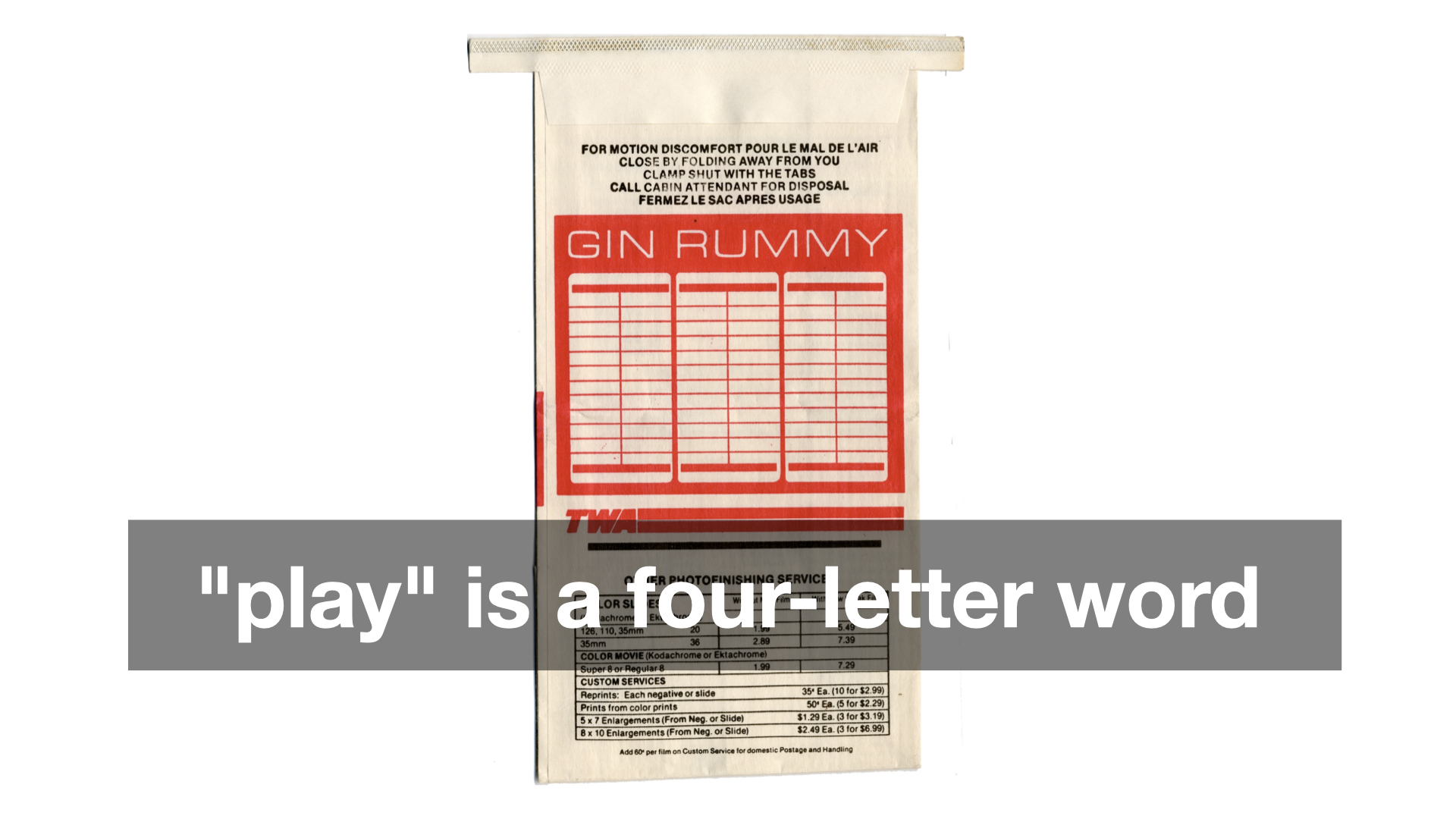

For example, I am not sure how many people would look kindly on the 600 air sickness bags in our collection saying things like this even if, despite the gag, it is an invitation to consider some of the larger questions around museum collecting practices. And air sickness bags.

Earlier in this talk I said One of the challenges that digital technologies has made manifest in cultural heritage organizations is that there is more stuff than anyone has the time, attention or ability to devote to.

But we have opened that Pandora's Box and I don't think there is any closing it now.

If we're not going to put all of those objects back in to storage, hiding them away from view, and it is understood that left uncontextualized in our already media-saturated environment, those objects are robbed of the weight they deserve then... what? Answering that question is, in fact, what I think the future of museums

looks like in 2024.

I do not want to suggest that technology devices like the Pen, social media accounts, generative content or play, silly jokes and puns are the sole, or even the correct, answers to these questions. As I said at the very beginning I think the right

answer is creating conditions where objects are able to be revisited again and again (and again). The examples I've shown today are simply some attempts, among many, to try and do that: To use these tools in conjunction with ideas like an on-going curatorial file meant for public consumption, as a way demonstrate proof of life in our collections and to allow the public to engage with them on playing fields they recognize and understand.

I'd like to end this talk with a passage from the introduction to Emily Wilson's translation of The Iliad:

Another traditional narrative technique prominent in The Iliad is the use of lists or catalogs. To a reader unaccustomed to the norms of modern prose, these passages may look off-putting on the page. Read them out loud: in mouth and ear, the long lists of names become music. Catalogs also serve to evoke the vast scale of the war and the world, and to gesture towards all the many people and events that are omitted from the narrative. The Catalog of Ships is long, but it suggests that there are many times more people at Troy than can ever be named. The poet needs something more than a normal human voice to tell such a vast story:

I could not tell or name the multitude

not even if I had ten tongues, ten mouths

a voice that never broke, a heart of bronze...Catalogs give a human singer something like ten tongues; they enable a single poem to encompass the whole world and remember all the numberless dead.

Thank you.

This blog post is full of links.

#usf