Wishful Thinking

I spoke at the 2023 Museum Computer Network conference, in Philadelphia, last week and presented a talk titled Wishful Thinking – A critical discussion of "extended reality" technologies in the cultural heritage sector

. These are my notes for the talk. This is what I was planning to say sticking to these notes closely enough (because the talk was only 15 minutes) that I expected people would notice. I said as much at the beginning of the talk but by the time I reached the second slide I realized that I had neglected to make sure that the display setup allowed me to see my notes. It did not and it was too late to do anything about that so I did the talk from memory. I missed a few points that I wanted to make but, somehow, still managed to capture the gist of it.

I want to take a moment to acknowledge that we are rounding the corner on the first anniversary of the death of Effie Kapsalis. Many of the people at MCN this year will have known or worked with Effie. For those of you who didn't, her's is a name worth remembering. Effie is probably best known for being the spearhead and the public face of the Smithsonian's Open Access Initiative but she did so much more during her time and by those efforts she made us all, both individually and as a professional community, better.

This is a short talk for a big subject. As such it is possible some old man yelling at the sky

vibes might happen and for that I'd like to apologize in advance and invite you to find me after the talk to discuss the nuances and finer points of the subject.

It's a big subject because what I really want to talk about today is not so much a particular set of technologies but what those technologies represent for the cultural heritage sector.

In order to do that I am going to trot out of a trio of elephant-sized ideas and then leave them standing awkwardly in the corner. Each one of these ideas is an entire conference in its their right. We don't have time for that today but it is important to call out these ideas because they are the basis, and the core set of beliefs, from which the rest of this talk extends.

The first is that the practice of revisiting is the bedrock of the humanities. Revisiting is what distinguishes entertainment from culture.

It is important to recognize that there is a time and a place for both things and that entertainment routinely becomes culture but that transformation occurs precisely in the very act of revisiting.

The second is that recall has always been a power dynamic.

You see this throughout history: In the right to assembly; In the question of access to basic literacy; The entire notion of a public library; The restrictions around intellectual property; Paywalls and the rights to broadcast or re-broadcast.

Whether it's been through malice or negligence or unintended circumstances the ability to not only see in to the future but see in to the past has not been an opportunity open to all.

Third, technology is a reflection of worldview. This is a generally true statement, I think, but it is especially true with regards to these last two points. How you think about the role and the function of technology is a pretty good mirror on how you think about the questions of recall and revisiting.

I am going to come back to this idea at the end of the talk because I think it is crucially important to the cultural heritage sector in a moment where we seem to be living through another technological phase-shift.

But first I am going to travel back in time to Museums and the Web 2013. (I actually said and believed this was MCN 2013 until I started writing this blog post. Oh well...) This is a photograph of the inflatable unicorn head that I brought to the panel discussion on humour and institutional voice that I was a part of.

After the panel I was approached by a recent museum studies graduate who asked for advice on getting started and developing a public persona in the sector. Although they never said these exact words what I heard was:

How do I as a person who is new to a small and often insular community develop the means to express controversial, or at least unorthodox, opinions without burning all my bridges before I've even gotten started?

I do not think that I am especially well-qualified to answer that question. The reality is that I arrived in the museum sector with a reputation, or at least credentials, that preceded me and this was a great privilege not enjoyed by all.

What I tried to explain to this person, though, was that quite a lot of that reputation was made possible by having been present on and participating with the web. Without the web most of my peers and I would never have enjoyed the audiences or the reach for the ideas and projects, some of them serious and many of them goofy, that we pursued.

Importantly, being present on the web was not, and has never been, a guarantee of a receptive audience or even any audience at all.

On the other hand the web made those things possible in a way that had never existed before. What that means practically is that it was easy and cheap enough to put something on the web and then to leave it there long enough for others to find it, after the fact.

Not free but compared to the limited avenues available to people before the web you could almost pretend that it was.

Already back in 2013, though, you could feel like something was changing. It was a change, one actively advanced and promoted by social media companies in the decade to follow, that's come to largely define how people think about doing anything online, even today.

Namely that if you publish something online – whether it's a selfie, a "hot take", an essay or a multi-year project; anything really – and it is not immediately successful or viral then it was a waste of time and effort. It was not worth doing.

Which is insane. It is insane because that's not how ideas take root.

It takes people time to warm up to ideas, especially new or challenging ideas, if only because we are busy just juggling the ideas and beliefs we already hold with the complexities of our lives in relation to one another.

It is also hard not to understand this idea as a deliberate of attempt to gaslight the web and everything that makes the web important.

So let's take a moment to review what makes the web important and novel.

Not only is the web a global network of linked documents unbounded by geography but, critically, it is asynchronous.

Not only can you access the web from anywhere but you can do so at anytime. The technology for these three things to exist in tandem may have pre-dated the web but they had never been realized in concert, at the scale of the entire planet, before the web.

Both HTML, the format used to encode documents on the web, and HTTP, the mechanism to deliver those documents from a server to a browser, are radically simple in their design.

It is true that, in 2023, the web has evolved to eye-watering degrees of complexity in order to allow for higher-order functionality like streaming video, advanced layouts and fancy animations.

But the core of the web, the design for deploying a network of linked documents, of words and ideas, remains simple enough that most people can create a web page in day and many people could build a rudimentary but functional client or a server in a weekend.

And this. This is a screen capture of the opening ceremony at the London Olympics in 2012.

It might be hard to see but that's a little house in the middle of the stage and inside that house was Tim Berners Lee, the creator of the web, sitting at a desk in front of a computer. The script called for him to type a message in a web page which was then lit up in the seats around the arena. That message read:

This (meaning the web) is for everyone.

When Berners Lee first announced the web, he also announced that it was being released without any use or licensing restrictions.

Aside from the corniness of the setup at the Olympics it's hard to overstate how big a deal this was. It's taken me a long time to really appreciate what those actions represented. He put the means to deploy an asynchronous and global network of linked documents in the hands of everyone. For free.

When you consider the media landscape that both predates the web and that continues to dominate our lives, one defined by a handful of companies exercising a disproportionate influence on what can be said, when it can be said and by whom it is hard not to understand the web as an intensely political act.

It is worth remembering that the internet, and the web in particular, happened

to the media and technology companies that existed at the time.

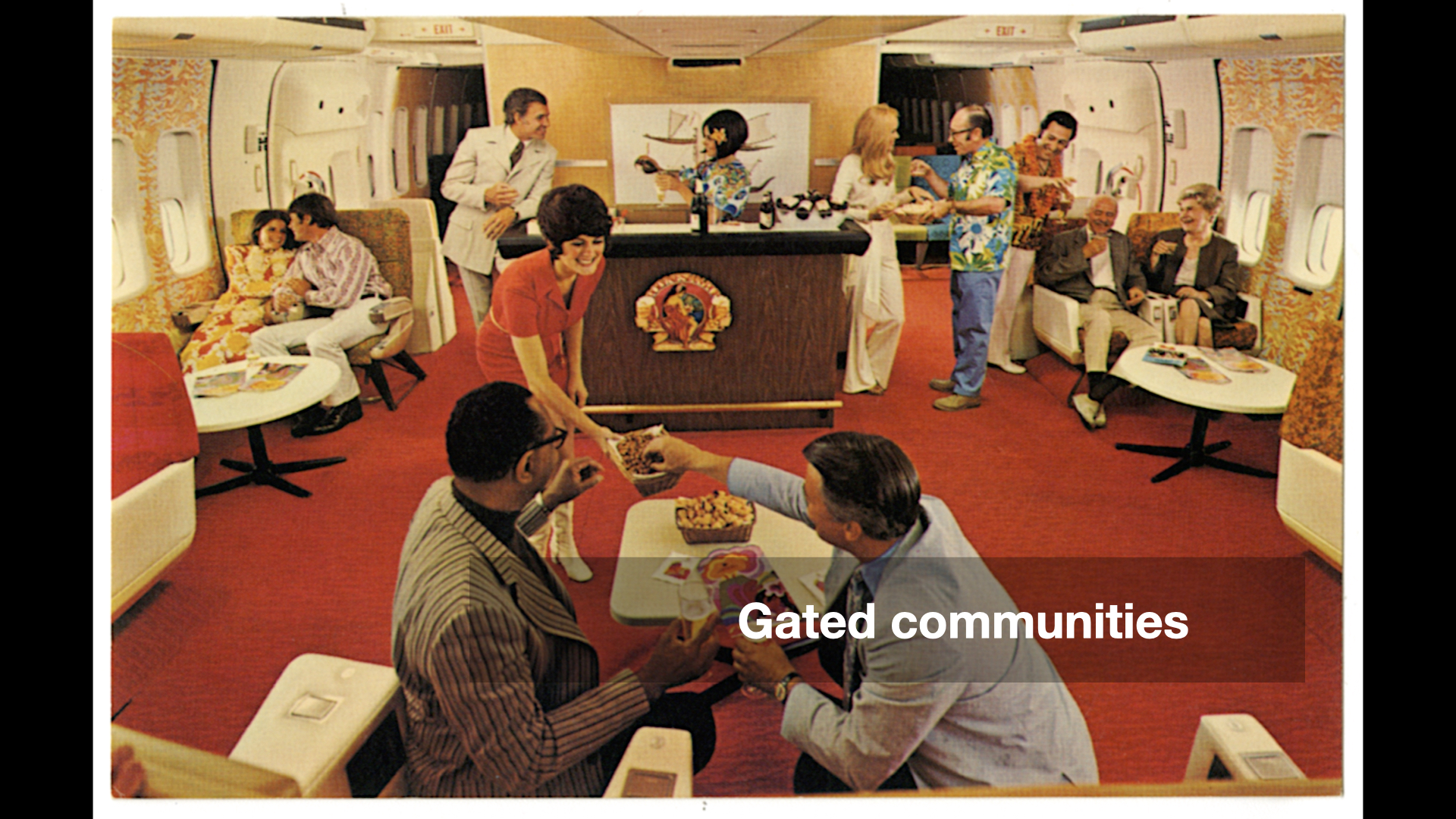

In as much as any of them were imagining what a universe of networked computers might look like they did not imagine the web. What they imagined, what they were actively promoting and marketing, were a series of branded communities, of walled gardens, with only limited means to interact with one another.

When the web first landed in people's lives neither Apple nor Microsoft had native TCP/IP stacks, TCP/IP being the networking layer that makes the internet work. People had to install third-party TCP/IP software (using floppy disks or some other kind of removable media) just to make the web work but they did, in droves, and it wasn't long before that kind of functionality became table stakes for all operating systems.

Since then the old media companies and the newer technology companies, which have become increasingly indistinguishable from one another, have embraced the web after a fashion but only as a kind of stepping-stone to bring people back to in to the fold of proprietary wall gardens.

Case in point: Mobile phones and the "app economy", an environment controlled by exactly two companies and designed to extract a commission from almost every interaction and to promote native and not-portable applications over web applications. But we also see the same behaviour from so-called "born of the web" companies like Facebook who have explicitly monetized reach, access and discovery. Facebook is also the company that gave the world React which is difficult not to understand as deliberate attempt to embrace and extend, to redefine, HTML itself.

Perversely, nearly everything about the mobile/app economy is built on, and designed to use, HTTP precisely because it's a common and easy to implement standard free and unencumbered by licensing.

The recent history of the web, of the internet, has largely been defined by companies engaged in various forms of extractive behaviour, first with their customers but increasingly amongst themselves. Facebook for example is still trying to recover from, and adapt their business model to, Apple's decision to deny them access to the vast swathes of customer data that previously they harvested from people's iPhones and resold.

Which brings us to virtual, extended or augmented reality and the so-called metaverse

. There are lots of different, valid ways to think about this idea of extending space, activity and community in to virtualized, generative and networked environments. The possibilities are, both literally and figuratively, endless.

But it would be naive not to understand the recent push towards virtual technologies, advanced by the same companies that have dominated the internet landscape for the last decade as anything but more of the same, just with a hypothetical reshuffling of the gate-keepers.

If it is already hard to complete with companies like Facebook or Instagram, because they enjoy such commanding slices of the marketplace, what "VR" heralds is more of the same but with a technical footprint so expensive and so demanding that it all but ensures it will only be within the means of a very few companies to operate.

Apple's recently announced Vision Pro headset is, by all accounts, a marvel of hardware design and software integration. It is Apple at its very best. It also represents 20, probably even 25 years, of ongoing research and development and product launches. Look at the Vision Pro device and then look at the last ten years of hardware and software releases and it is nearly impossible not to see the outlines of the device taking shape in plain sight.

It is also one of the most terrifying pieces of technology I've seen in the last decade. When you stop to consider everything it claims to do, it is a near-perfect surveillance device and the history of miniaturization in electronics coupled with the push towards wearable and embedded computing suggests, at the very least, a haunting future on the horizon.

Honestly, the only thing to save this device is the trust that Apple has marketed its brand on over the last few years. But a brand promise is about as fleeting a guarantee as you can get and there is a limit to the kinds of hardware controls you can bake in to these devices to ensure that promises of security and privacy are kept. Any sensor, or recording device, connected to the internet will forever be a tempting fruit.

Speaking of which since the launch of the VisionPro, Facebook has updated their own virtual reality headset to include front-facing cameras to enable the same kind of "pass-through" functionality that the Vision Pro offers. "Pass-through", as the name implies, allows you to see the physical world around you in concert with augmented, or mixed, reality experiences.

But who here believes that Facebook doesn't have other motives for enabling an always-on camera capturing the world around you? In case you need any reminding this is the company that gave the world the Cambridge Analytica scandal which, really, is just the tip of the iceberg.

Facebook it is also worth noting has, in the span of just three years, hired and then fired 10,000 people to work on their "metaverse" initiative. It has reportedly spent upwards of a billion dollars already and, still... they haven't figured out how to render legs faithfully.

Meanwhile, Microsoft has gotten out of the consumer virtual reality headset market entirely. Snap recently shut down their commercial services AR division. Even Google has pulled back from headsets in the years since the launch of the ill-fated Google Glass.

It remains a challenging space. If any company is able to realize the technical vision of virtual reality and make it compelling enough for people to use then the rewards stand to be significant but, as I mentioned, not many companies will succeed and the world we will live in will look very much like the world of the big broadcast networks that existed before the web.

So let me be blunt:

The cultural heritage sector, on the other hand, can barely afford to hire and retain the staff necessary to keep a single website running for more than five years, let alone a decade or the twenty years we'll imagine it took to launch the Vision Pro headset.

It stands to reason then that in as much as we choose to engage with these new platforms it will never be on our terms and it will only ever be a commercial and a rent-seeking transaction.

Historically, the museum sector has used technology as a proxy to validate its efforts. We keep an eye on what's "cool" and "new" and then we integrate those technologies in to our programming as a way to stay, or at least appear, relevant.

In 2023, the web is not "cool" anymore. It's not clear whether extended reality technologies are cool yet but there is definitely a concerted effort to try and make them seem that way. The point I have been driving at in this talk is that a funny thing happened thirty years ago:

The web happened and while it was absolutely the new, shiny, cool thing at the time it also happened to be the technology that most closely aligns, by design and by intent, with the purposes and motivations of the cultural heritage sector.

The web is the means by which the acts of revisiting and recall of our collections, our programming and our institutional histories have become technically feasible, economically viable and with a reach and on a schedule that has literally never before been possible.

We would do well to recognize that. We would do well to understand the web not just as a notch in the linear progression of technological advancement but, in historical terms, as an unexpected gift with the ability to change the order of things; a gift that merits being protected, preserved and promoted both internally and externally.

The point is not that our relationship with technology should end with the web. The point is the web allows us to reframe our relationship with technology. Importantly, it enables – it does not guarantee, but it enables – us to reframe our relationship and dependence on the providers of those technologies.

The challenge of that relationship lies in the fact that as often as not the motivations of those providers and their platforms are not our own. Yet we continue to make an increasingly Faustian bargain to engage with them because we believe that these places are where our audiences have gone. Sooner or later that debt will come due so we would do well to recognize that the alternative, and a good alternative at that, is within our grasp.

Failing that, maybe the passing of the web can at least be the prompt we need to stop pretending that our relationship with technology is anything but window dressing.

Thank you.

This blog post is full of links.

#wishful